This is one of the things I did for fun and did it with only my memory and imagination as company. It’s an old habit: writing fragments of obsession that I started years ago and keep coming back to when I’m feeling heavy or restless. When I finished Fragments of Obsession V: What Remains of Him, I knew there was still more to figure out—more shadows, more tenderness, and more moments haunted by tragedy. So I let myself return to his rooms, his silences, and his gaze, and I wrote a few more. This is what play looks like for me now. This is not an escape but a way for me to process past experiences and to turn them into gentle longing, finally tame and set free.

Riverside

I fall behind pretending I care about the river, when all I really want to do is watch him move ahead. He never misses anything. His hands in his pockets and his shoulders tight. But then he slows down, turns around, and gives me that look, like he’s been waiting for me all his life. I see that half-smile he only gives me. It almost feels private, something he keeps to himself and lets slip just for me.

I could live in that space between us just for the thrill of him staying still and making me want to get closer. He doesn’t say my name. He never does. He stands there with his boots on, the city and river catching in the leather of his jacket, making him look both real and unattainable.

He watches every step I take. He doesn’t fill the gap. He makes me feel the anguish of wanting to be closer. He let me reach him and let me be the one to move first. He tilts his head, keeps his eyes focused and drawls softly, “Took you long enough.”

I can’t help it. I smile. Because I know I’ll always keep chasing him, and he’ll always let me find him.

His Apartment

His apartment is nothing like I imagined, though in some ways it’s exactly what I expected. There are books all over the place. Some were stacked, some were abandoned in the middle of a thought, and some had bent pages where he stopped reading. When he isn’t looking, I run my fingers along the spines and read the titles like clues. I wonder about the books he returns to, those he doesn’t finish, and the ones he holds close. I try to picture which lines he remembered and which sentences he underlined in his mind.

His boots are next to the door, with the laces loose and the toes pointing out like he kicked them off without thinking. There’s a mug on the table with a faint coffee ring drying at the bottom. I pick it up, turn it slowly, and picture his mouth there. I always do that—touch the things he touched, like maybe I can learn something from him that he doesn’t say.

A jacket hangs off the chair, slumped over and heavy in the shoulders. It looks worn out. I wonder how long it’s been carrying him like that. A scarf draped carelessly over the back, still holding the shape of his neck. I don’t touch it. I don’t want to change how he left it.

There are pictures by the window. I look at them when he’s in the other room. Family. People I don’t know. I study them for too long, trying to remember their faces and figure out where he came from and what made him who he is now. He doesn’t explain them. I don’t ask. But my mind keeps going around and around them, restless and unfulfilled. I want to know who he was before he learned how to hold back.

In the morning, sunlight spills over the rug, revealing dust, creases, and the signs of the days he’s lived without me. I see everything. The fact that he always puts his keys in the same place. The small pile of my belongings that have started to gather—a pen, a hair tie, and a notebook that I left on purpose and pretended was an accident. He never moves them.

When I sit on his couch, I pull the blanket over my legs and breathe in his scent. His smell is faint but stubbornly sticking to the fabric. There are dents in the pillows. I press my hand into the hollow and imagine how he fell asleep there on the nights he was too exhausted to care.

In his bedroom, the bed is never made. The sheets were twisted, and the blankets were half fallen to the floor. A shirt is hanging over the chair, and the sleeves are knotted like it was taken off in a hurry. I lie there and stare at the ceiling, counting the cracks and listening to the city breathe outside. Here, my body relaxes in a way it doesn’t anywhere else. Here, his hands don’t have to hold evidence, or grief, or anything but me.

At night, I watch him sleep. I memorize how he breathes, the slight pause before it settles. I tell myself that I will remember it later. That’s what I always think. Like memory is something I can stockpile.

In the morning, the light climbs the wall slowly, indifferent. I know I’ll be leaving again. I do it all the time. But I also know that I leave parts of myself behind that are too small to see but impossible to take back. A strand of hair in his bed. A warmth that stays even after my body is gone. A familiarity he’ll feel later and not know why.

His apartment is not mine. But my desire is everywhere in it. And every time I leave, I can’t help but think that I know him better through his absence than his words.

Haunted

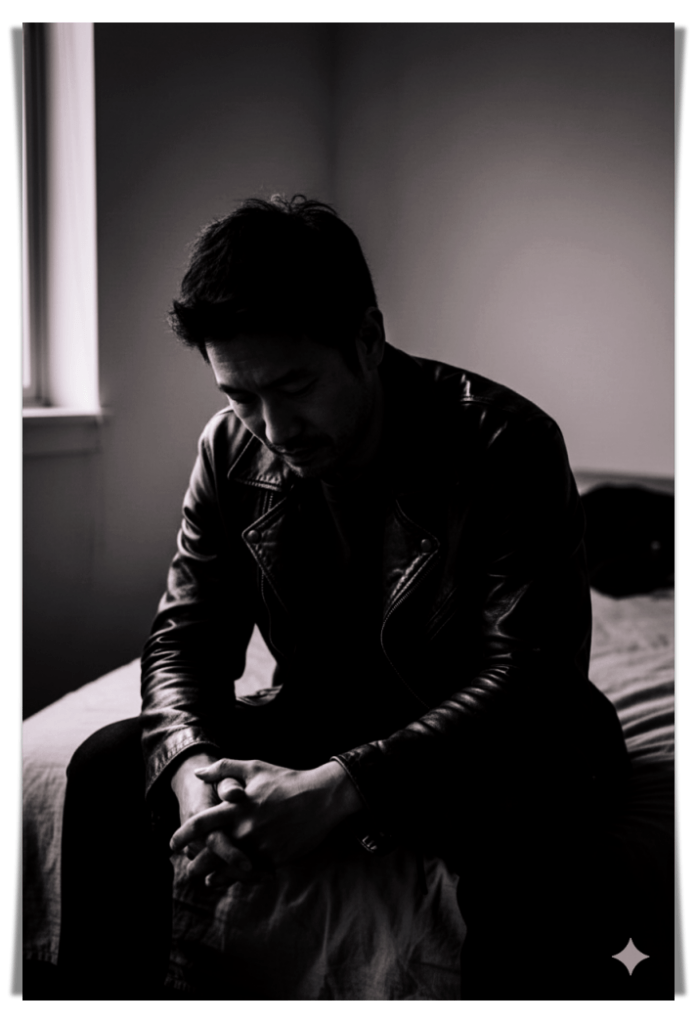

He comes in late, and the door closes quietly behind him. He doesn’t turn on the main lights; instead, he lets the dusk hang softly between us. His shoulders are hunched under the old leather jacket, and I know right away that something heavy followed him home. I can tell by the way he takes off his boots and the silence he carries with him.

He sits on the couch, elbows on his knees, head bowed, and hands dangling. There is blood on the edge of his shirt cuff, but it might not be his. I see how his fingers flex and how he runs a hand through his hair. He’s not with me yet. Still stuck in whatever he saw and can’t say out loud.

This is how I remember him: the hollows under his eyes, the day-old stubble on his jaw, the cut on his knuckle from a door he probably shouldn’t have punched. I look at him and see the small tremor in his hands and the shallow breaths he inhaled. He stares at the wall instead of me.

He doesn’t talk about work, at least not the real stuff. But the story always creeps into the room, clinging to his skin, hair, and the distance between us. I want to reach out to him, pull the darkness off his back, and hold all the sorrow he tries to hide. But I don’t. I just watch and let myself memorize him when he’s like this: unreachable, falling apart, but still here.

He finally looks up, and there’s something wild in his eyes. A flash of pain that isn’t meant for me but finds me anyway. I take it all at once. I tell myself that if I can remember him like this, haunted and broken, then nothing the world throws at us will ever make me forget him.

So I keep watching. I let my eyes linger, wanting to see every scar and every unnamed pain. I keep watching until he starts to come back, when his breathing slows and his hands stop shaking. And when he finally looks me in the eye, it feels like apologies and resignation to survive.

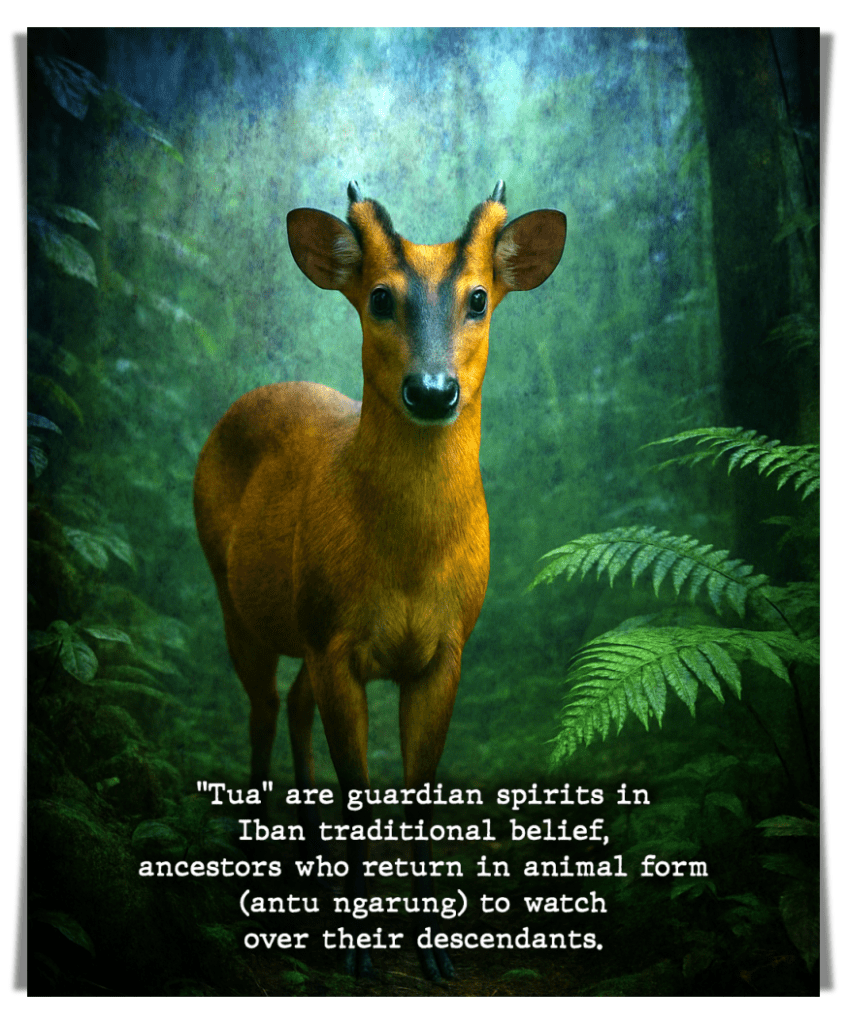

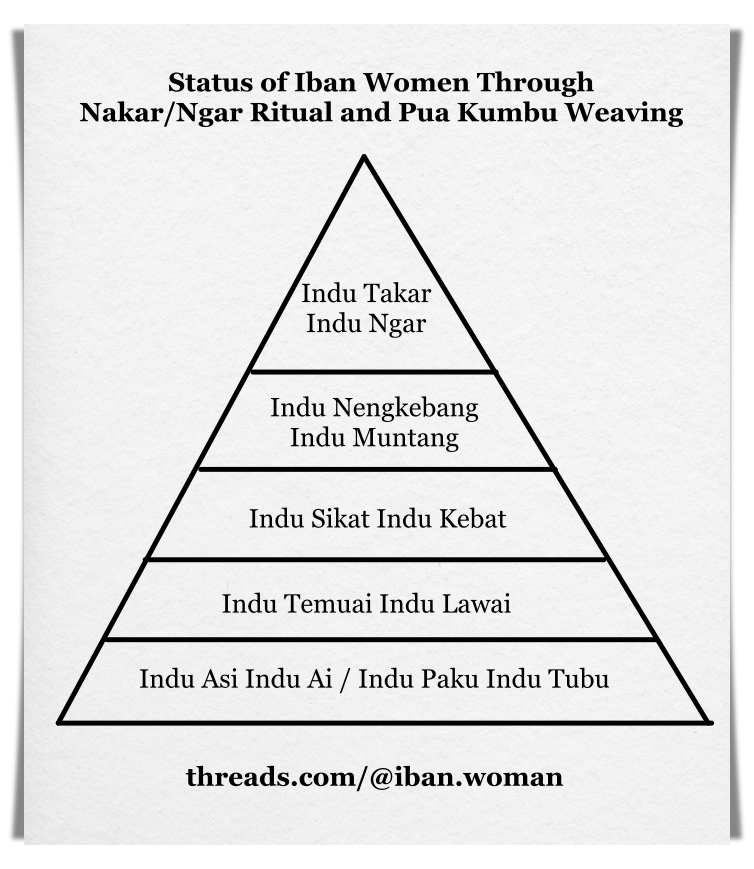

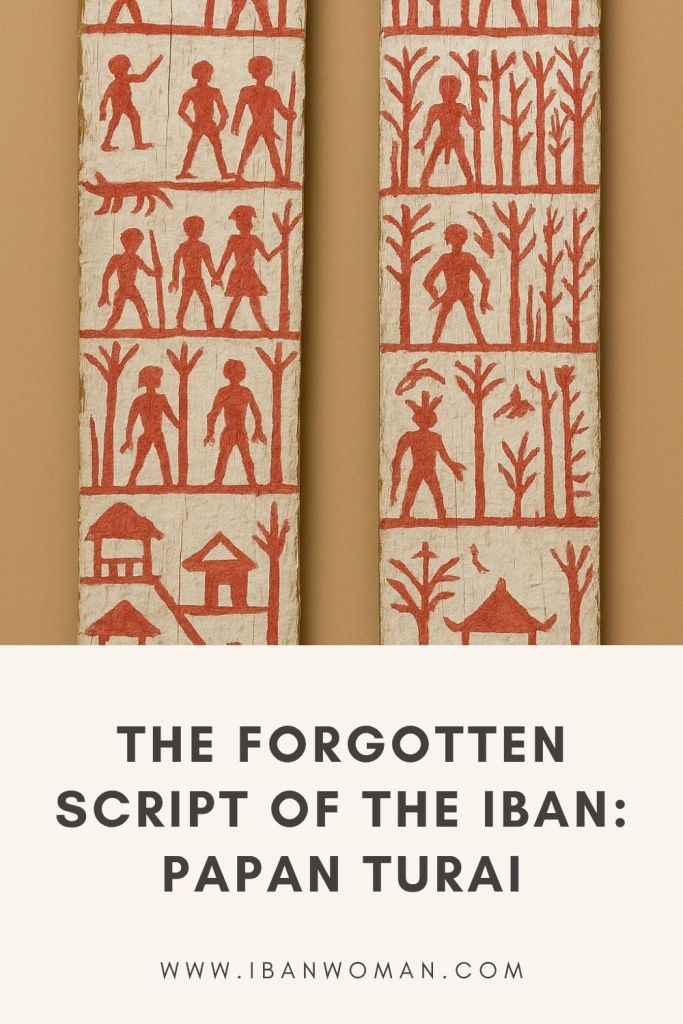

I write about Iban culture, ancestral rituals, creative life, emotional truths, and the quiet transformations of love, motherhood, and identity. If this speaks to you, subscribe and journey with me.